After two years of decline during the pandemic years, global insolvencies increased by 9% in 2022. The increase was related to the halting of Covid fiscal support packages and the lifting of temporary changes to insolvency legislation. In some markets, insolvencies have completely normalized or even exceed pre-pandemic levels. But in the majority of countries, we observe that insolvencies are in the process of adjusting back to pre-pandemic levels. For 2023 we predict an increase of 49% in the global level of insolvencies, as ‘return to normal’ continues. In 2023 we are seeing rising insolvencies across all regions, with North America experiencing a relatively strong increase, while Europe is seeing milder increases. The majority of countries in each region can expect rising insolvencies this year. In 2024, the picture is more mixed. On a global level, we predict that insolvencies rise by 12% compared to 2023. In most markets that we observe, insolvencies are expected to have more or less normalised in 2024.

Subdued global GDP growth expected in 2023 and 2024

The global economy is forecast to grow only 1.7% in 2023. This year global monetary tightening and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continue to drag on the world economy, bringing the US and Europe in particular to stagnation. Inflation has begun easing across major markets, but generally remains above central bank targets. Central banks in Europe and the US are therefore expected to keep policy rates at current high levels and possibly increase rates even further. High inflation, tight financing conditions and dwindling savings buffers suppress demand. In 2024, declining inflation and improved consumers’ purchasing power puts the global economy in a better position. We therefore foresee a slightly higher GDP growth of 2.5% in 2024.

Emerging markets as a group are forecast to grow by 3.2% in 2023 and 4.2% in 2024. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and tighter financial conditions weigh on GDP growth across EMEs. Emerging Asia remains the fastest growing region (4.4%). Chinese GDP growth has been revised upwards to 4.5% in 2023 as Covid restrictions have been largely abandoned. A more “proactive” and “pro-growth” government policy is likely to support Chinese private consumption in 2023. At the same time, demand will still be constrained by the property sector slump and weak consumer confidence. In Eastern Europe, the outlook continues to be dominated by the Russia-Ukraine war. Western countries have imposed massive sanctions on Russia, leading to another year of recession there in 2023. The powerful earthquakes that hit Turkey on February 6th are another setback for Turkey and the wider region. The Turkish economy was already struggling with high inflation and lira depreciation, and the economic impact of the earthquake constrains Turkish GDP growth further in the near term.

Growth in advanced economies is just 0.7% in 2023, with 2024 only forecast to be slightly better at 1.2%. The United States economy had a better than expected GDP growth in Q4 of 2022. However, as private consumption has been consistently losing pace, we think it likely that in the second half of 2023 the US economy briefly enters a recession. This brings GDP growth to slightly below 1% in both 2023 and 2024. For the eurozone, the overall picture is one of weak economic growth and substantial downside risks. The most recent estimate of eurozone Q4 GDP indicates that growth has come to a standstill. We are also cautious about the growth outlook for the rest of 2023 as high energy prices and the war in Ukraine continue to weigh on growth. Furthermore, the effects of the monetary tightening underway have yet to be fully felt. We forecast a relatively weak growth in 2023 (0.6%), followed by a slightly better growth in 2024 that is just above 1%.

While government fiscal support related to the pandemic has been largely phased out, the overall fiscal position continues to be expansionary in most advanced markets. Several countries have adopted support packages to counter the negative effects of the rise in energy prices, which gives some support to economic growth. However, there are also new risks, which are mainly the result of recent monetary policy tightening. Major central banks such as the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB) have implemented significant policy rate hikes in the past year. This recently contributed to unrest in the banking sector, with several regional US banks filing for bankruptcy. In Europe, the banking sector looks more robust, but this did not prevent Credit Suisse, a bank with long-standing issues, to be forced into a takeover by the Swiss regulator. Events like this may make central banks more cautious in implementing further rate hikes. If current market tensions do not subside, central banks may very well pause their monetary policy tightening going forward. Credit standards have tightened in both the US and the eurozone in recent months.

The tightening of financial conditions in advanced markets also has spillover effects to emerging markets. Several emerging markets have experienced sharp currency depreciations since the Federal Reserve started to increase interest rates. In particular countries with high private debt levels (e.g. Turkey) are vulnerable to the tightening of financial conditions.

Insolvencies are adjusting back to pre-pandemic levels

After two years of convincing insolvency declines - which were due to pandemic support packages and temporary changes to insolvency legislation by countries laws - the global number of insolvencies increased by 9% in 2022.

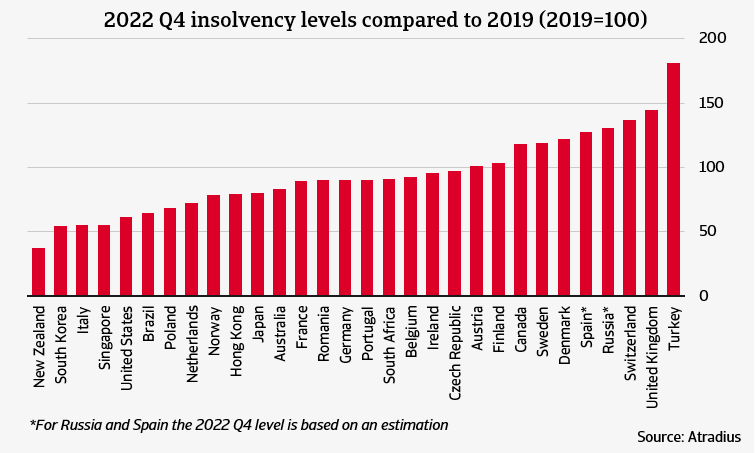

Chart 1 compares the 2022 Q4 insolvency data to the same period in 2019. A value above 100 indicates that the insolvency level in a country is above the (pre-pandemic) 2019 level. A value below 100 means the insolvency level is still lower than in 2019.

We consider a market to have adjusted fully back to ‘normal’ if the index value is at least 95%. This is the case for Turkey, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Russia, Spain, Denmark, Sweden, Canada, Finland, Austria, Czech Republic and Ireland. In the majority of markets, however, the adjustment back to normal is still underway. This means insolvency levels remain below the 2019 level.

The list of countries for which the insolvency level in 2022 Q4 was relatively high should not come as a complete surprise. In Turkey, for example, the economy is suffering from high inflation, depreciation of the lira and high corporate debt. In the United Kingdom, the rise of insolvencies can be attributed to ending of government support measures and the weak economic recovery since Brexit. In Switzerland, it is also attributed to the discontinuation of government support and the associated bankruptcy of zombie firms. In Spain, the economic slowdown and the lifting of the moratorium on bankruptcy filings triggered a spike the insolvency level in Q3 of 2022. A new insolvency law that makes it easier for companies to restructure their debt may help in the future to cut high bankruptcy rates. Denmark, Sweden and Czech Republic did not experience a strong decline in insolvencies during the pandemic, suggesting that government support perhaps was somewhat weak or ineffective.

Countries with relatively low insolvency counts relative to pre-pandemic are, for example, New Zealand, South Korea, the United States and the Netherlands. These are all countries which had generous corona support measures, which increased firms’ liquidity. We believe that these cash buffers prevented a rise of insolvencies immediately after the government support measures were phased out. As a result, the insolvencies levels in these countries remained low relative to pre-pandemic.

Outlook for full year 2023: a continuation of the adjustment to normal

We base our forecasts for 2023 on the idea that countries will see their insolvency levels return to ‘normal’ levels with pandemic-related fiscal support being discontinued. We assume that it can take up to eight quarters after government support is discontinued before the insolvency level reaches the normality level. On top of the normalisation, we distribute on the forecasting horizon additional defaults coming from zombie companies. The latter are likely to occur because in the pandemic period the insolvency levels contracted well below their pre-pandemic levels. We believe that these companies will default after the government support is withdrawn.

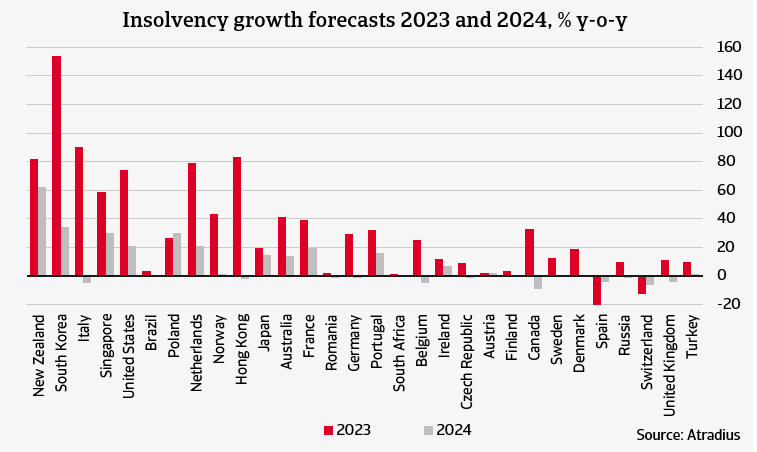

We now turn to our insolvency forecast for 2023 and 2024, which is given in year-on-year % changes (e.g. 2023 compared with 2022). On a global level, we predict that insolvencies increase by 49% year-on-year in 2023. On a regional level, we foresee a relatively strong increase of insolvencies in North America (71%), which is mainly driven by the United States. For Europe, we expect a relatively mild increase of 27% as the process of normalisation of insolvencies in Europe is already more advanced compared to other regions. For Asia Pacific we predict an increase of 56%.

Chart 2 presents our insolvency forecast for 2023 and 2024 on a country level. The markets are arranged in the same order as in Chart 1. The highest insolvency growth rates in 2023 are recorded in South Korea, Italy, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Netherlands and the United States. The shared characteristic is that all these countries have a very low insolvency level in 2022 compared to the pre-pandemic situation. For these countries, the adjustment to normal largely takes place in 2023. This, in combination with the bankruptcy of zombie firms, pushes up insolvency growth in 2023.

There are also markets with relatively low or negative insolvency growth in 2023. Countries for which we expect a decline in insolvencies in 2023 are Spain and Switzerland. In these countries the insolvency level has increased throughout 2022 to above the normality level. In 2023, we forecast a decline, such that the insolvency level moves closer to the normality level. Countries for which we expect relatively mild insolvency growth include several European countries where insolvencies have already normalised in 2022, such as Austria, Finland, Czech Republic and Sweden.

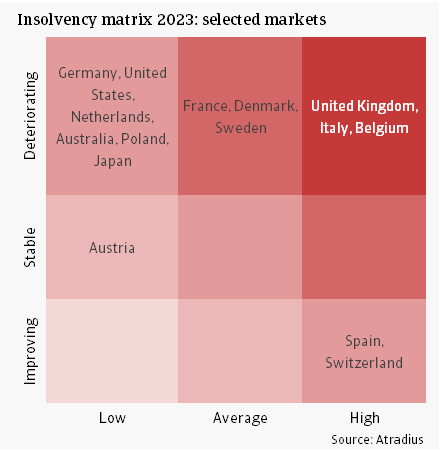

Chart 3 shows the insolvency developments across another dimension. The vertical axis of the insolvency matrix shows the year-on-year expected change of insolvencies in 2023 compared to 2022. Insolvency growth considered ‘Deteriorating’ if growth is higher than 2%, ‘Stable’ if it is between -2% and +2%, and ‘Improving’ if it is lower than -2%. The horizontal axis shows the level of insolvencies in 2023 compared to 2019. This gives a better impression how the current level of insolvencies compares to the pre-pandemic level. We identify the level as ‘High’ if in 2023 it is expected to be above 120% of the 2019 level, ‘Average’ if it is between 95% and 120%, and ‘Low’ if it is below 95%.

For the majority of countries, the trend is deteriorating in 2023, but the overall level remains low compared to the pre-pandemic level. Spain and Switzerland are the only two countries with an improving insolvency trend, as indicated in the previous paragraph. The United Kingdom, Italy and Belgium are in the most worrisome position from the selected markets, as the trend is deteriorating in 2023 and the insolvency level in 2023 is moving above 120% of the 2019 level. The UK is a particularly interesting case as insolvencies already returned to normal, pre-pandemic levels in 2022, together with the bankruptcy of zombie firms. However, the low growth environment is expected to push insolvencies even higher in 2023. In Belgium, the normalisation of insolvencies started in 2022 and is continuing in 2023. In Italy, the adjustment is very much taking place in 2023, leading to a deteriorating trend.

Outlook for full year 2024: a more mixed picture

In 2024, the picture is more mixed. On a global level, we predict that insolvencies rise by 12% compared to 2023. We see a rise of insolvencies in a number of countries (New Zealand, South Korea and Singapore) where the normalisation continues. However, we also see that in many markets insolvencies will again start to decline or remain approximately constant. This is because insolvency levels will have largely returned to normal and zombie firms that are not able to survive without support, have gone bankrupt already.

Countries with a negative expected insolvency growth in 2024 are, for example, Switzerland, Canada and Russia. In Russia, there is an overshooting of insolvencies in 2023, due to the economic effect of the war with Ukraine and the sanctions that are imposed on Russia. In 2024 insolvencies will partially normalise as the economic situation stabilises. In Canada, there is an overshooting of insolvencies in 2023, largely due to the bankruptcy of zombie firms. In 2024 the situation in Canada also partially normalises. In Switzerland, 2024 brings another year of decrease in insolvencies, as the insolvency level continues to move to a normality level that is comparable with the 2019 level.

The coming years are likely to remain challenging for firms. They have to survive in an environment without the same generous government support that was received during the pandemic. Moreover, they face an environment with significantly tighter financing conditions, which is likely to be a challenge for firms that have taken up a lot of debt during the pandemic.

Theo Smid, Senior Economist

theo.smid@atradius.com

+31 20 553 2169

All content on this page is subject to our Disclaimer, available here.

- We expect insolvencies to increase globally in 2023, driven by continued normalisation after the pandemic and the bankruptcy of zombie firms. This is against a macroeconomic backdrop of high inflation, monetary tightening and less significant government support than during the pandemic years. For 2024 we expect a year of relative stabilisation.

- In 2023, we expect sharply rising business failures in South Korea (154%), Italy (90%), Hong Kong (83%), New Zealand (82%), the Netherlands (79%) and the United States (74%).

- In 2024, we forecast relatively high insolvency increases in New Zealand (62%), South Korea (35%) and Singapore (30%).